There’s been discussion circulating about the upcoming City Council President selection and what “tradition” should apply. Let’s look at what was actually decided through the democratic process.

In September 2024, the City Council passed Charter Amendment Resolution No. 24-19, which was introduced by Mayor Michael O’Connor and approved after extensive review by a Charter Review Committee.

This amendment specifically created a NEW process for selecting the City Council President, effective December 1, 2024. According to the resolution, “at its first meeting in December 2024, and thereafter on the first business day of a new term of office, the City Council shall elect from its membership a City Council President and Vice President.”

This wasn’t a sudden change—it was a deliberate, public process that went through proper channels. The amendment replaced the previous § 9, making that old section “of no further force or effect.”

The current process isn’t breaking tradition—it IS the new tradition, established through the proper democratic and legal process before any votes were cast.

When we discuss what the council “should” do, we need to start with what the actual governing documents say, not assumptions about how things used to work.

The voters elected their representatives. Those representatives amended the charter through proper procedures. Now that same council will follow the charter they themselves approved.

That’s not changing the rules—that’s following them.

The Role of City Council President: What Really Matters

Core Responsibilities to Consider:

When electing a council president, members should be asking themselves critical questions about governance, not politics:

- Legislative Management

- Can this person effectively manage council meetings and keep discussions productive?

Do they understand parliamentary procedure well enough to ensure fair process?

Can they balance allowing robust debate while moving business forward?

Will they ensure all voices are heard, even dissenting ones?

- Can this person effectively manage council meetings and keep discussions productive?

- Relationship Building

Can this person work with the Mayor’s office, even when there’s disagreement?

Do they have the temperament to build consensus among diverse council members?

Can they maintain professional relationships with department heads and city staff?

Will they represent the council effectively in negotiations and intergovernmental relations? - Strategic Vision

Does this person understand the city’s long-term challenges and opportunities?

Can they help the council set priorities and stay focused on them?

Do they have the experience to anticipate consequences of policy decisions?

Can they think beyond individual projects to systemic city governance? - Crisis Management

When controversial issues arise, can this person keep the council functioning?

Do they have the judgment to navigate politically sensitive situations?

Can they maintain public confidence in city government during difficult times?

Will they make decisions based on the city’s best interests, not personal political calculation? - Institutional Knowledge

Does this person understand how the city actually operates?

Do they know the budget process, departmental structures, and existing policies?

Can they hit the ground running, or will there be a steep learning curve?

Have they demonstrated commitment to understanding the complexities of city government? - Communication Skills

Can this person articulate the council’s positions clearly to the public?

Do they communicate effectively with colleagues in ways that build trust?

Can they translate complex policy into language residents understand?

Will they be accessible and responsive to community concerns? - Time and Commitment

Does this person have the availability to fulfill the additional responsibilities?

Will they prioritize council leadership when it conflicts with other obligations?

Can they attend the extra meetings, events, and functions the role requires?

Do they understand this is a service role, not just a title?

Why This Isn’t a Popularity Contest

The president doesn’t govern alone – they facilitate fi ve or seven or nine other elected officials doing their jobs effectively. A popular president who can’t build consensus accomplishes nothing. An effective president who isn’t the most charismatic can help the entire council serve the city well.

Consider this:

Popularity is about individual appeal. It’s about who gives the best soundbites, who has the most name recognition, who generates the most enthusiasm. Popularity wins elections – and it should. That’s democracy.

Leadership is about collective function. It’s about whether the council can work together, whether meetings are productive, whether the city’s business gets done efficiently and transparently. Leadership makes governance work.

The council already has fi ve (or seven) people who won popularity contests – that’s how they all got elected. Every council member earned their seat by connecting with voters. Every council member brings constituent voices to the table.

But the presidency isn’t another election – it’s a job assignment.

Think of it this way: A hospital wouldn’t make their most popular doctor the chief of surgery. They’d choose the surgeon who can manage the operating room, coordinate the surgical team, handle complications, and ensure every patient gets excellent care. Bedside manner matters for doctors; operational excellence matters for chiefs.

Similarly, a council shouldn’t elect their president based solely on vote totals. They should elect the person who can:

- Run efficient meetings

Build working relationships across ideological differences

Navigate confl icts between council members

Represent the council professionally in external relationships

Understand complex policy well enough to guide productive discussion

Make the entire council more effective

The voters chose the council members. Each member’s electoral success gives them equal legitimacy at the table and equal voice in decisions. The council president doesn’t get extra votes. They don’t override the majority. They serve the council’s collective function.

The council chooses its president – and they should choose based on who will help them govern most effectively.

What Effective Leadership Looks Like

An effective council president:

- Serves the institution, not themselves. They ensure fair process even when they disagree with the outcome. They protect minority voices even when they’re in the majority. They maintain the council’s credibility even when it’s politically costly.

- Builds bridges, not fi efdoms. They fi nd common ground between competing interests. They translate between different communication styles. They create space for compromise without sacrifi cing principle.

- Focuses on outcomes, not optics. They measure success by what gets done, not by how many headlines they generate. They’re willing to work behind the scenes if that’s what moves things forward.

- Empowers colleagues, doesn’t eclipse them. They create opportunities for other council members to lead on their priorities. They share credit. They make the whole council look good, not just themselves.

- Maintains perspective. They remember they’re one voice on the council, with one vote. They don’t confuse the role’s visibility with having more power. They stay humble.

The Real Question Before the Council

When council members enter that vote, they shouldn’t be asking: “Who got the most votes?” They already know who won their races.

They should be asking:

- “Who will help us work together most effectively?”

“Who has the experience to navigate the challenges we’ll face?”

“Who will represent our collective decisions well, even when they personally disagree?”

“Who will make me a better council member?”

“Who will help this council serve our city most effectively?”

Those questions require looking beyond popularity to leadership capacity, beyond vote totals to governance skills, beyond individual appeal to collective function.

A Final Thought

The best council president might be the person who got the most votes. Electoral success can indicate many qualities useful for leadership – constituent connection, communication skills, community trust, political acumen.

But electoral success doesn’t automatically equal leadership effectiveness. And if the council determines that another member is better equipped to facilitate their collective work, that’s not disrespecting the voters – that’s the council doing exactly what the charter empowers them to do: making the best decision for effective governance.

The voters chose the players. The charter asks the players to choose their captain. Both choices matter. Neither is more legitimate than the other. They’re just different decisions, serving different purposes, in a well-designed democratic system.

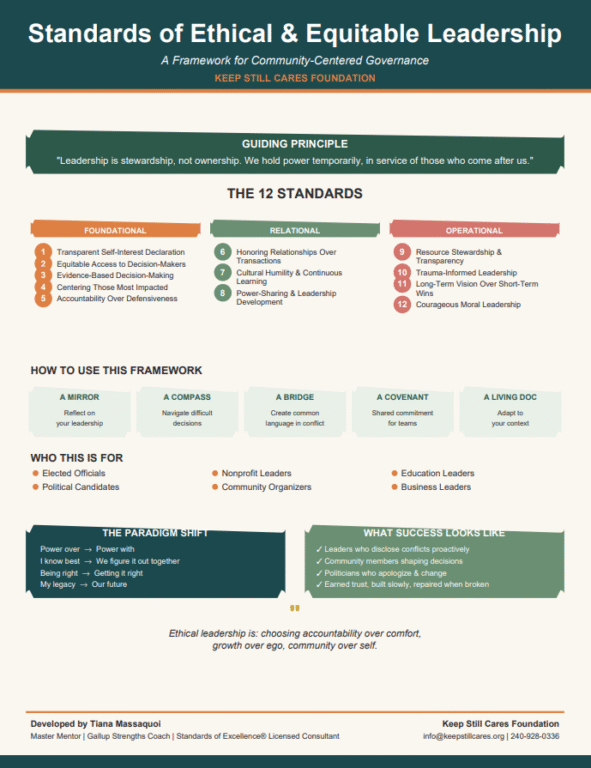

Tiana Renee is a community-based accountability facilitator, emergent strategy practitioner, and youth advocate. As co-founder of Keep Still Cares Foundation and Technical Assistance Consultant with MENTOR Maryland DC, she champions youth development and mentoring. Tiana believes we all have a responsibility “to encourage a young person, today!”

Article Photo Credit: Visit Frederick